Revenue Mobilization Africa (RMA), in partnership with the Centre for Environmental Management and Sustainable Energy (CEMSE), has raised concerns over how the erstwhile government handled the banking sector clean-up exercise, and the lack of transparency on how much has been recovered by the Attorney-General and Minister of Justice, Dr. Dominic Ayine.

RMA and its partners, following a recent announcement by the Attorney-General and Minister for Justice, Dr. Dominic Ayine, that the office has entered a nolle prosequi in the criminal prosecution of former Governor of the Bank of Ghana and former Finance Minister, Dr. Kwabena Duffour, and seven others of defunct UniBank, raised concerns over what they describe as limited transparency and inadequate recovery of the funds injected into collapsed financial institutions.

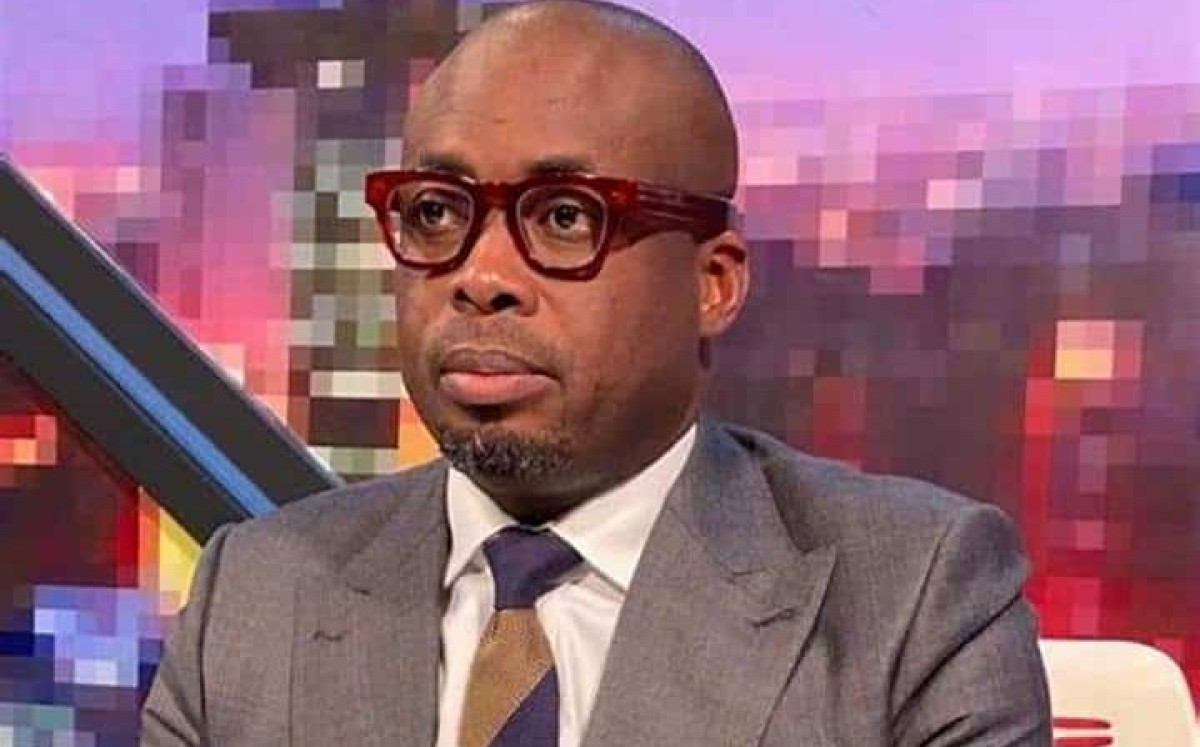

Addressing the press at the International Press Centre in Accra on Friday, August 1, 2025, under the theme: Banking Sector Clean-Up: Demand for Accountability and Reform in Ghana’s Financial Sector”, the Executive Director of Revenue Mobilisation Africa, Geoffrey Kabutey Ocansey, noted that although the AG has outlined the broad outlines of the settlement with UniBank’s former directors, the public remains largely uninformed about the specific terms and timelines.

He therefore urges the Minister of Finance and the Bank of Ghana to expedite efforts in publishing the full details of all agreements and the status of recovery, thus far.

“We call on the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Ghana to publish the full details of all agreements and the status of recovery so far,” he noted.

Highlighting the discrepancies in the data leading to the dissolving of UniBank, RMA stated, “Before the revocation of UniBank’s license, the Government of Ghana owed the bank approximately GHS 2.9 billion, held in bonds, treasury bills, and other instruments. The bank was placed under administration for six months under Act 930 (Banks and Specialised Deposit-Taking Institutions Act), a provision specifically designed to rehabilitate banks and prevent collapse, not to dissolve them.”

“The indebtedness of Unibank as at the beginning of 2025, per court records, was GHC2.8billion. In 2024, the former Attorney General Godfred Dame, through the receiver of Unibank, amended the total validated indebtedness of Unibank from GHC 5.7billion to GHC 2.8billion. The GHC5.7 billion circulating in the news in recent times is therefore not justified by the existing records”, Mr. Ocansey further stated.

He further stated, “A further validation by the current Government of the GHC2.8billion figure brought the amount to GHC2 billion in the year 2025. We were also eager to condemn revenue losses that might emanate from the said 60-40 recovery arrangement, but as the above-narrated facts show, that was also inaccurate.”

According to the Civil Society Organisation (CSO), committed to promoting transparent and effective mobilisation of public resources maintained that beyond UniBank, there is no clear national accounting of what has been recovered, how assets have been managed or disposed of, and what remains outstanding.

“This raises a real risk of financial loss to the state and the Ghanaian taxpayer,” Mr. Ocansey said.

Read Full Statement Below:

RMA Press Statement

Revenue Mobilisation Africa

Banking Sector Clean-Up: Demand for Accountability and Reform in Ghana’s Financial SectorGood morning, Ladies and Gentlemen of the press;

Revenue Mobilisation Africa (RMA) and partners acknowledge the recent decision by the Attorney-General to enter a nolle prosequi in the criminal prosecution of former officials of UniBank, and the state’s attention also towards a structured recovery of public funds lost through banking sector failures.

As civil society organisations committed to promoting transparent and effective mobilisation of public resources, we welcome all efforts that lead to the recovery of lost public funds. The ongoing restitution arrangement, through which over GHS 824 million in property has already been transferred by UniBank, with a further GHS 1.2 billion expected, marks a positive step towards accountability and the restoration of public resources.

However, we wish to raise important concerns about the long-term implications of how the Government (the previous administration) has handled the banking sector clean-up, particularly with regard to:

1. Revenue Losses and Public Debt ExposureThe clean-up exercise, while was argued necessary to stabilise the financial sector, cost the state over GHS 25 billion. These funds were largely mobilised through domestic borrowing and have significantly increased the national debt burden.

To date, there has been limited transparency and inadequate recovery of the funds injected into collapsed financial institutions. Beyond UniBank, there is no clear national accounting of what has been recovered, how assets have been managed or disposed of, and what remains outstanding. This raises a real risk of financial loss to the state and the Ghanaian taxpayer.

2. Lack of Clarity in Settlement TermsAlthough the AG has outlined the broad outlines of the settlement with UniBank’s former directors, the public remains largely uninformed about the specific terms and timelines. We call on the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Ghana to publish the full details of all agreements and the status of recovery so far.

3. The facts as of today – what we know so far.

Before the revocation of UniBank’s license, the Government of Ghana owed the bank approximately GHS 2.9 billion, held in bonds, treasury bills, and other instruments. The bank was placed under administration for six months under Act 930 (Banks and Specialised Deposit-Taking Institutions Act), a provision specifically designed to rehabilitate banks and prevent collapse, not to dissolve them.

The indebtedness of Unibank as at the beginning of 2025, per court records, was GHC2.8billion. In 2024, the former Attorney General Godfred Dame, through the receiver of Unibank, amended the total validated indebtedness of Unibank from GHC5.7billion to GHC2.8billion. The GHC5.7 billion circulating in the news in recent times is therefore not justified by the existing records.

A further validation by the current Government of the GHC2.8billion figure brought the amount to GHC2 billion in the year 2025.

We were also eager to condemn revenue losses that might emanate from the said 60-40 recovery arrangement, but as the above narrated facts show that was also inaccurate.

4. Outstanding questionsLadies and gentlemen, we are gravely concerned about the total cost of the banking sector clean-up, which reportedly exceeded GHS 25 billion.

Given that the actual indebtedness of UniBank was not GHC5.7billion as presented by the Auditor who later became the Receiver, but GHC2.8billion and 2.0billion upon further validation, the following pertinent questions need asking;

Why did the Attorney General initially approve or support a debt figure of GHS 5.7 billion that was later reduced to GHS 2.8 billion, and now reportedly to GHS 2 billion?What harm did the inflated figure cause to the state and the stakeholders?Was the original GHS 5.7 billion figure used to justify certain state actions or asset seizures that are now invalid?To the receiver, was there overstatement or misrepresentation of liabilities?To the receiver again, were state assets, decisions, or funds wrongly committed based on the incorrect figures?

Was the state’s legal position thoroughly verified before initiating legal action and defending the bank’s closure in court?If incorrect financial data was used in court proceedings, could this expose the state to damages or liability?Did the Attorney General act in the best interest of the state, or did they enable actions that resulted in the destruction of jobs, potential tax revenue, and public confidence?

What efforts were made to recover the GHS 2.9 billion owed by the Government to UniBank before or during the administration process?Did the state’s failure to pay its debts to UniBank amount to negligence or reckless disregard for the bank’s solvency?What has happened to UniBank’s assets since the receivership?Have they been sold, transferred, or devalued below market price?Can the Receiver account for the disposal of these assets?How much has the receivership process cost the state in legal fees, administration fees, loss of tax revenue, and employment?Were these costs justifiable compared to the cost of recapitalisation?Did the Receiver properly follow the provisions of Act 930 aimed at rehabilitating banks before moving to liquidation?If not, was this a violation of law?

6. DemandsLadies and gentlemen, we now move on to our demands to the current Government.

Demand for a Full Independent Public InquiryGovernment should constitute an independent commission of inquiry to investigate:

The role of the Bank of Ghana, the Attorney General, and the Receiver in the revocation of UniBank’s license.The shifting figures of validated liabilities (from GHS 5.7b to GHS 2.8b and now GHS 2b).The state’s failure to acknowledge the GHS 2.9 billion owed to the bank during the cleanup.

Legal and Criminal AccountabilityThe government should initiate legal proceedings against any public official, including the Attorney General and the Receiver, who:

Knowingly misrepresented financial facts.Caused willful financial loss to the state.Enabled or participated in the mismanagement, undervaluation, or improper disposal of assets of the bank (UniBank).

Reversal of Questionable Asset TransfersThe government should investigate and, where necessary, reverse or nullify any transfers or sales of UniBank assets that occurred:At below-market pricesFor the benefit of politically connected individuals or companies

Review of Receiver’s ConductThe government should conduct a forensic audit of the Receiver’s work:How assets were handledHow liabilities were calculatedWhether liquidation was necessary or a result of bias.Legislative and Institutional Reform

Parliament should amend Act 930 to ensure:Greater checks and balances on the Bank of Ghana’s powers to revoke licenses.Mandatory parliamentary oversight when the Central Bank moves to close major banks.Establish a Bank Resolution Ombudsman or Financial Sector Justice Board to handle future bank crises independently of political interference, like the Financial Ombudsman Service of the UK or the Ombudsman for Banking Services of South Africa.

Call to Action to Other Key StakeholdersIn light of the grave concerns highlighted above and the serious implications for national revenue, justice, and public trust, we put forward the following urgent call to action to the following key stakeholders:

To the Private Sector;Speak out in defence of fair and transparent business practices. Demand reforms that protect investments and businesses from arbitrary state actions. Unite to ensure that no legitimate enterprise is destroyed without due process. A secure and predictable financial system is vital for private sector growth and national development.

To Civil Society Organisations (CSOs)Mobilise public awareness, demand accountability, and join your voices to the call for institutional reform. This is a critical time to challenge the misuse of state power and ensure justice for affected citizens and businesses. Use every platform to push for transparency, justice, and the protection of constitutional rights.

To Organised Labour and Workers’ UnionsStand in solidarity with the hundreds of employees who lost their livelihoods due to the collapse of UniBank and the other banks with similar situations. Demand justice for affected workers and reforms that guarantee job security and protect workers from the consequences of flawed financial governance. Workers’ voices must be part of the national demand for justice and accountability.

ConclusionThe collapse of UniBank, underpinned by questionable decisions, shifting financial figures, and a lack of transparency, raises serious concerns about governance, accountability, and the potential for misuse of state power.The actions and inactions of key public officials, including the Attorney General and the Receiver, did not only deprived shareholders and depositors of justice but may also have caused significant financial loss to the state.To restore public confidence, uphold the rule of law, and prevent future abuses, the government must act decisively. This includes initiating an independent inquiry, pursuing legal accountability, and reforming institutional processes. Anything less would be a grave betrayal of the principles of justice and responsible governance.